Defending Prophet Sulaiman (AS): A Union of Legitimacy and Divine Wisdom

Prophet Sulaiman (AS), a noble messenger of Allah, was granted immense wisdom, authority, and control over creation as a divine favour. His rule was marked by justice, faith, and submission to Allah. Among the many historical discussions surrounding his life, some sources speculate about a union between him and Bilqees, the Queen of Sheba/Saaba. While Islamic scripture does not confirm such a marriage, it is essential to address the question of legitimacy from an Islamic perspective.

Marriage as a Means of Legitimacy

Islam upholds marriage as the only lawful means for lineage and inheritance. If Sulaiman (AS) had a son—though the Qur'an and Hadith do not confirm this—it would be unthinkable that such a child was born outside of wedlock. As a prophet, Sulaiman (AS) would never engage in anything unlawful or contrary to divine guidance.

The Qur’an affirms that all prophets were chosen for their righteousness and unwavering commitment to Allah’s commands:

"They are those whom Allah has guided, so follow their guidance..." (Surah Al-An’am 6:90)

This guarantees that Sulaiman (AS) would have upheld the sanctity of marriage in any relationship he pursued.

Prophetic Honour and Moral Integrity

Islamic teachings reject any notion of illegitimacy associated with prophets. Allah Describes prophets as examples of morality and purity:

"And We certainly sent before you messengers, and We made for them wives and descendants..." (Surah Ar-Ra’d 13:38)

This verse reaffirms that prophets had lawful marriages and offspring, ensuring that their lineage was always legitimate. Any claim that suggests otherwise contradicts the divine protection and honour Allah Bestows upon His messengers.

Conclusion

From an Islamic standpoint, Prophet Sulaiman (AS) remains beyond reproach. If he had a son, it would have been through a lawful union, as prophets are divinely guided and preserved from moral failings. The Qur’an and Sunnah uphold his integrity, wisdom, and commitment to justice, making any suggestion of illegitimacy baseless and contrary to Islamic teachings.

The Union of Sulaiman (AS) and Bilqees: A Catalyst for Monotheism in Africa

The story of Prophet Sulaiman (AS) and Bilqees, the Queen of Sheba, is often viewed through the lens of political alliance and spiritual transformation. While the Qur’an does not explicitly confirm their marriage, historical and extra-Islamic sources suggest that their union had a lasting impact, particularly on the African continent. This perspective refutes the notion that their relationship was a mere fling, instead highlighting how their union played a crucial role in the spread of monotheism and the transformation of religious beliefs across regions such as Ethiopia and Yemen.

Bilqees’ Acceptance of Monotheism

The Qur’an (Surah An-Naml 27:44) details Bilqees’ recognition of the One True God after witnessing Sulaiman’s wisdom and miraculous abilities. She declared:

"My Lord, indeed I have wronged myself, and I submit with Sulaiman to Allah, the Lord of the worlds."

This conversion was not just personal but marked a shift for her kingdom, which had previously practised sun worship. Her acceptance of monotheism suggests that she played a role in guiding her people toward faith, mirroring the pattern of influential female rulers who brought religious transformation.

The Spread of Monotheism into Africa

The region of Sheba (Saba) is historically linked to Yemen and Ethiopia. The idea that Bilqees’ union with Sulaiman (AS) influenced the spread of monotheism is supported by the following historical developments:

The Judeo-Converts of Ethiopia – Ethiopian history traces the origins of its Jewish community (Beta Israel) to the union of Sulaiman and Bilqees. According to Ethiopian tradition, their son, Menelik I, established the Solomonic dynasty, which ruled Ethiopia for centuries and maintained a connection to Judaic traditions. This suggests that the knowledge of monotheism, likely through the Mosaic faith, reached the region long before Christianity and Islam.

Transformation of South Arabian Religion – Archaeological and historical studies show that pre-Islamic South Arabia, including the Sabaean kingdom, gradually moved from paganism to monotheistic influences. The decline of polytheistic worship in this region aligns with the timeline of Bilqees’ reign and the possibility of her people adopting faith-based reforms.

Christianity and Islam in Africa – When Christianity arrived in Ethiopia in the 4th century CE and Islam in the 7th century CE, the transition to monotheism was notably smoother compared to other regions. This suggests an already existing familiarity with the concept of One God, possibly dating back to earlier influences from Sulaiman and Bilqees’ era.

Conclusion

The relationship between Sulaiman (AS) and Bilqees was not a fleeting romance but a momentous alliance that had long-term religious and cultural consequences. Whether through direct lineage or influence, their connection contributed to the gradual replacement of pagan traditions with monotheistic beliefs across Africa and Arabia. This historical legacy reinforces the significance of their union beyond personal ties—it was a divinely guided moment in history that helped lay the groundwork for future Abrahamic faiths in the region.

Misar in the Quran: Egypt’s Name and Its Linguistic Legacy

Egypt holds a unique place in history, culture, and religion, with its name appearing in the Quran as "Misar" (مصر). Unlike other lands, Egypt is the only country explicitly mentioned by name in the Quran, reinforcing its historical and spiritual significance. However, the name "Misar" in Arabic differs from both the ancient indigenous name "Kemet" and the Greek-derived "Egypt." Exploring these names reveals a fascinating linguistic evolution tied to Egypt’s identity across civilizations.

Misar in the Quran: A Singular Mention

In multiple Quranic verses, Egypt is referred to as "Misar" (مصر), most notably in the story of Prophet Yusuf (Joseph, peace be upon him) and the Exodus of Bani Isra'il.

One of the most famous mentions is in Surah Yusuf:

وَقَالَ ٱلْمَلِكُ ٱئْتُونِى بِهِۦ أَسْتَخْلِصْهُ لِنَفْسِى ۖ فَلَمَّا كَلَّمَهُۥ قَالَ إِنَّكَ ٱلْيَوْمَ لَدَيْنَا مَكِينٌ أَمِينٌۭ

“And the king said, ‘Bring him to me that I may appoint him exclusively for myself.’ And when he spoke to him, he said, ‘Indeed, you are today established [in position] and trusted [by us].’” (Quran 12:54)

The term "Misar" refers to Egypt as a distinct nation, unlike other lands that are mentioned descriptively rather than by name. In classical Arabic, "Misar" also means a settled land, a metropolis, or a civilizational center, reflecting Egypt’s status as a hub of civilization.

The Name "Kemet": The Land of Black Soil

Ancient Egyptians referred to their land as "Kemet" (𓆎𓅓𓏏𓊖 - km.t), meaning "Black Land." This name was likely inspired by the rich, dark silt deposited by the Nile, in contrast to the barren "Deshret" (Red Land) of the desert.

"Kemet" was an indigenous name rooted in the land’s fertility, emphasizing Egypt's dependence on the Nile. It was widely used by the civilization itself but did not persist in later historical records as dominion over Egypt changed hands multiple times.

From "Hwt-Ka-Ptah" to "Egypt"

The name "Egypt" comes from the Greek "Aigyptos" (Αἴγυπτος), which traces its origins to the ancient Egyptian phrase "Hwt-Ka-Ptah," meaning "House of the Ka (spirit) of Ptah." This phrase referred specifically to the temple of Ptah in Memphis, one of Egypt’s earliest religious centers.

Through Greek influence, "Hwt-Ka-Ptah" transformed into "Aegyptus" in Latin, later becoming "Egypt" in English. Thus, while "Egypt" is internationally recognized today, it is a foreign adaptation, unlike "Kemet" or "Misar," which are more directly connected to the land’s original identity.

Misar vs. Kemet vs. Egypt: Which is More Accurate?

Each name holds significance depending on context:

"Misar" (مصر) – The Quranic and Arabic name, highlighting Egypt’s enduring identity in Islamic tradition.

"Kemet" (𓆎𓅓𓏏𓊖) – The indigenous name, reflecting the land’s agricultural wealth and self-identity in ancient times.

"Egypt" (Aigyptos/Aegyptus) – The modern name, stemming from Greek and later European influence.

If discussing Egypt from a Quranic perspective, "Misar" is most authentic. If focusing on ancient Egyptian history, "Kemet" is correct. For modern political and geographical references, "Egypt" is the standard designation.

Conclusion

Egypt’s name has evolved across languages and cultures, yet its legacy remains unchanged. The Quranic term "Misar" connects Egypt to divine history, "Kemet" ties it to its indigenous roots, and "Egypt" reflects its global recognition. Each name tells a story, shaping our understanding of this ancient land that has captivated civilizations for millennia.

Ancient Egypt (Kemet) was deeply interconnected with its African neighbours, and its success was shaped by exchanges with Nubia (Kush), Punt, Libya, and other African civilizations. Below is a linear timeline of Egypt’s dynasties, highlighting not only its rulers but also the contributions of neighbouring African nations.

The Dynastic Timeline of Kemet & Africa’s Influence

1. Predynastic Egypt (c. 5000–3100 BCE) – The Foundations

Proto-Pharaohs: Scorpion King, Narmer (Menes)

African Influence:

Nubia (Kush) provided gold, cattle, and early cultural influences, seen in similar burial practices.

The people of the Sahara (pre-Libyan Berbers) and Sudan contributed domesticated animals and agricultural techniques.

2. Early Dynastic Period (c. 3100–2686 BCE) – The First Kingdom

Dynasties 1–2 (Narmer, Hor-Aha, Djer)

African Influence:

Unification of Upper and Lower Egypt likely influenced by Nubian and Saharan trade networks.

Punt (modern Eritrea/Somalia) provided incense, ebony, and exotic animals—highly prized in Egyptian rituals.

3. Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BCE) – The Pyramid Age

Dynasties 3–6 (Djoser, Sneferu, Khufu, Khafre, Menkaure, Pepi II)

Contributions from African Neighbours:

Nubian gold mines fueled Egypt’s economy.

Punt’s trade routes became vital for incense, used in religious ceremonies.

Libyan (Tjehenu) warriors served in Egyptian armies.

4. First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE) – Regional Rule

Egypt fragmented, and Nubian rulers in Kerma (Sudan) gained power.

Thebes (Upper Egypt) would later reunify the land.

5. Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BCE) – Expansion & Nubian Integration

Dynasties 11–12 (Mentuhotep II, Amenemhat I, Senusret III)

African Contributions:

Nubians became generals and officials within Egypt.

Pharaohs fortified Nubia, building fortresses in Kerma to control trade.

Kushite influence in religion grew—many Egyptian gods (Amun, Hathor) had Nubian roots.

6. Second Intermediate Period (c. 1650–1550 BCE) – Hyksos and Nubian Power

Nubians (Kushites) expanded their rule over Upper Egypt.

Egypt adopted Kushite archery techniques—the Nubian bowmen were legendary warriors.

7. New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE) – Egypt’s Golden Age

Dynasties 18–20 (Ahmose I, Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Akhenaten, Tutankhamun, Ramesses II)

African Influence & Contributions:

Hatshepsut’s expedition to Punt brought gold, myrrh, and exotic goods, strengthening cultural ties.

Nubian viceroys ruled Kush as part of Egypt, showing strong African integration.

Ramesses II fought against Libyan tribes, who later merged into Egyptian society.

8. Third Intermediate Period (c. 1070–664 BCE) – Libyan & Kushite Pharaohs

Dynasties 21–25 (Libyan and Kushite rule)

African Contributions:

Libyan kings (Shoshenq I) ruled Egypt, showing deep North African integration.

The Nubian 25th Dynasty (Kushite Pharaohs) – Piye, Shabaka, Taharqa, and Tantamani restored Egypt’s greatness.

Kushite Pharaohs revived pyramid building, aligning more with African traditions than later Greeks and Romans.

9. Late Period (c. 664–332 BCE) – Foreign Domination & African Resistance

Dynasties 26–30 (Saite, Persian, native Egyptian resistance)

African Influence:

Taharqa (Kushite king) defended Egypt against Assyrians, temporarily keeping Egypt free.

Nubia remained independent, later resisting Roman expansion.

10. Greco-Roman Egypt (332 BCE–641 CE) – The Decline of African Rule

Alexander the Great, Ptolemaic Dynasty (Cleopatra VII), and Roman rule.

Egypt’s African identity was suppressed, but Nubia (Meroë) thrived independently, preserving older Egyptian traditions longer than Egypt itself.

The Legacy: An African Civilization that Shaped the World

Egypt did not exist in a vacuum—it was deeply connected to Kush, Punt, Libya, and the Sahara.

African kingdoms provided military support, trade, and cultural exchange, shaping Egyptian society.

Egyptian religion, architecture, and philosophy influenced Greek, Roman, and Islamic civilizations, continuing its legacy today.

Egypt (Kemet) was not just an isolated wonder—it was an African success story, deeply rooted in Black, North African, and East African contributions that still impact the world today.

A Time Traveller’s Guide to Ibrahim’s Egypt – The Old Kingdom (c. 2500 BCE)

Welcome, fellow travellers! Set your dials, adjust your sand-resistant boots, and prepare for a journey back over four millennia to Kemet—a land of sun-baked stone, black earth, and the ceaseless pulse of the Nile. This is the world that Ibrahim (AS) stepped into: not the gilded decadence of later Egypt, but a raw, powerful civilisation, where stone and sweat shaped the first great empire of Africa.

The Landscape & Architecture

Forget the towering temples of Luxor or the golden masks of Tutankhamun—this is Old Kingdom Egypt, a time of rugged grandeur and monumental ambition. The skyline is dominated by the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza, its white limestone casing still smooth and gleaming under the merciless sun. Nearby, the enigmatic Sphinx—not yet half-buried in sand—sits with an almost knowing gaze, watching over the necropolis of kings.

The capital, Ineb-Hedj (White Walls), later known as Memphis, is not a city of lavish palaces, but a working capital. The buildings are made of mudbrick, their walls often whitewashed to reflect the heat. Streets are narrow, shaded by wooden awnings, with bustling markets selling everything from linen to lapis lazuli. At the heart of the city stands the Per-Nswt, the royal palace, an imposing but practical structure where the ruler, the Nswt-bity, governs.

Inside, walls are decorated with painted murals of daily life—farmers harvesting, fishermen pulling nets, craftsmen carving stone. Hieroglyphs, not just art but living text, line the halls, speaking of the divine order that holds Kemet together.

Beyond the capital, the great river Nile flows, its floodwaters bringing life. Farmers in reed sandals and kilts of flax tend to the crops, while fishermen cast their nets from sleek wooden boats. In the distance, black Nubian cattle graze under the watchful eyes of herders.

Fashion & Adornment

Step into the streets of Ineb-Hedj, and you’ll see a civilisation of linen, leather, and beads. The people of Kemet dress simply but elegantly.

Men wear white linen kilts, fastened with intricately woven belts. The wealthier the man, the finer and more transparent the linen, a silent display of status.

Women don long, figure-hugging dresses, often adorned with beaded netting or gold-thread embroidery. Their jewellery is bold—wide collar necklaces of turquoise, lapis, and gold, heavy bracelets, and earrings.

Nobles and officials are instantly recognisable by their elaborate wigs, scented with wax cones that melt slowly under the heat, perfuming the air with lotus oil.

The common folk? They keep it practical—simple linen wraps, bare feet or leather sandals, and shaved heads to keep cool.

And the Nswt-bity (king)? He is divine. He wears the Nemes headdress, striped in blue and gold, and the curved false beard that marks him as a living god. His sandals never touch the ground—servants roll out woven mats before his every step.

Homes & Interior Design

A wealthy Kemetic home is a blend of function and beauty. White-plastered mudbrick walls enclose open courtyards where families gather under woven reed canopies. Inside, the floors are covered in reed mats, and the furniture—low wooden stools, beds with woven rush matting, and chests of ebony and ivory—is designed to keep cool in the desert heat.

Tables are laid with alabaster bowls filled with figs, dates, and honey cakes, alongside beer and wine stored in clay amphorae. The scent of incense—frankincense and myrrh—fills the air, masking the ever-present dust of the desert.

At night, the homes are illuminated by oil lamps, their flickering light casting shadows on the painted murals of lotus flowers, hunting scenes, and the sacred Nile.

Religion & Ritual

The gods of Kemet are ever-present. Temples stand at the heart of every city, massive stone structures where priests perform daily rituals to ensure the balance of Ma’at—the divine order of the universe. Statues of the gods—Ptah, Hathor, and the falcon-headed Horus—are adorned with fresh garlands of lotus and papyrus.

But for Ibrahim (AS), this is a land of deep spiritual challenge. He walks among people who worship nature, the sun, the river, and the dead. Their belief in the afterlife is absolute—tombs are built with more care than houses, for eternity is far longer than life. He sees men and women making offerings, burning incense, and whispering prayers to spirits that cannot hear them. He does not bow, does not sacrifice, does not submit.

In this land of kings and gods, he is a man alone—a prophet of the unseen in a land ruled by stone deities.

Final Thoughts

Ibrahim (AS) did not enter a land of golden excess, but a gritty, thriving civilisation, built on the back of African ingenuity. Kemet is not an island—its borders touch Nubia, Kush, and the lands of Punt, drawing influence from its neighbours and sending its own culture outward. It is a land of builders, warriors, and farmers, a place where faith is carved into stone and where even a stranger with a message of one God can alter the course of history.

As we step back into our time machine, leaving the scent of lotus oil and river mud behind, we wonder—what whispers of Ibrahim (AS) still linger in this land? Did his presence plant a seed that would one day flourish? Only history can tell.

Time jump: Initiated. Destination: Present day.

Here’s the write-up again, formatted without tables for better readability:

Parallels Between Prophet Yusuf (AS) and Prophet Musa (AS) in the Quran

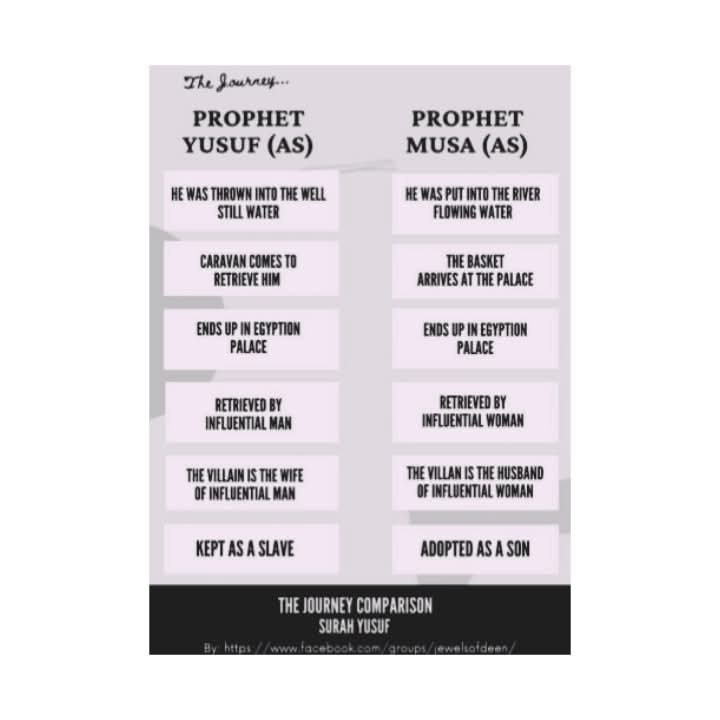

The journeys of Prophet Yusuf (AS) and Prophet Musa (AS) share striking similarities despite their distinct missions. Their stories illustrate themes of trials, resilience, and divine intervention. Below is a comparative analysis with Quranic references.

Early Life and Arrival in Egypt

Prophet Yusuf (AS) was thrown into a well with still water by his brothers (Surah Yusuf 12:15), while Prophet Musa (AS) was placed in a river with flowing water by his mother (Surah Al-Qasas 28:3-7).

A caravan retrieved Yusuf (AS) (Surah Yusuf 12:19), while Musa (AS)’s basket arrived at Pharaoh’s palace (Surah Al-Qasas 28:13).

Both ended up in the Egyptian palace—Yusuf (AS) as a servant (Surah Yusuf 12:21) and Musa (AS) as an adopted son (Surah Al-Qasas 28:8-9).

Yusuf (AS) was rescued by an influential man, Al-Aziz (Surah Yusuf 12:21), whereas Musa (AS) was rescued by an influential woman, Asiyah (Surah Al-Qasas 28:9).

The villain in Yusuf (AS)’s story was the wife of Al-Aziz, Zulaikha (Surah Yusuf 12:23-25), whereas in Musa (AS)’s case, the villain was Pharaoh, the husband of Asiyah (Surah Al-Qasas 28:4).

Yusuf (AS) was kept as a slave (Surah Yusuf 12:30-35), while Musa (AS) was adopted as a son (Surah Al-Qasas 28:9).

Isolation and Spiritual Growth

Yusuf (AS) was isolated in prison (Surah Yusuf 12:35-36), whereas Musa (AS) experienced isolation in the desert (Surah Al-Qasas 28:21-22).

In prison, Yusuf (AS) met two men and guided them spiritually (Surah Yusuf 12:36-41), while Musa (AS) met two women at the well and helped them (Surah Al-Qasas 28:23-24).

Men approached Yusuf (AS) for help in interpreting dreams (Surah Yusuf 12:36), whereas Musa (AS) was the one who approached the women for help in getting water (Surah Al-Qasas 28:23).

Yusuf (AS) helped others through interpretation of dreams (Surah Yusuf 12:41-42), while Musa (AS) helped through his physical strength (Surah Al-Qasas 28:24).

Yusuf (AS) preached to the men in prison about Allah (Surah Yusuf 12:37-40), while Musa (AS) did not preach but assisted practically (Surah Al-Qasas 28:24).

Reflections on Their Stories

The journeys of both prophets highlight:

Divine Wisdom in Trials – Yusuf (AS) and Musa (AS) faced hardship, but their struggles positioned them for greater roles.

Trust in Allah – Both relied on divine guidance in moments of uncertainty.

Service to Others – Whether through wisdom or physical aid, they served people in need.

Their stories remind us that hardship is often a stepping stone to greater purpose, and that trusting Allah leads to eventual success.

CONCLUSION:

The articles under Bridging the Horn of Africa collectively highlight the deep historical, religious, and cultural interconnections between Africa and the broader Islamic and Abrahamic traditions. They emphasize the legitimacy and moral integrity of Prophet Sulaiman (AS), particularly in relation to his possible union with Bilqees, Queen of Sheba, which is framed not as a mere romance but as a pivotal moment in the spread of monotheism across Africa and Arabia. This theme extends into the historical evolution of Egypt (Misar/Kemet), showcasing its ties with Nubia, Punt, and other African civilizations, reinforcing Africa’s role as a cradle of religious and civilisational development. The overarching takeaway is that Africa, particularly the regions surrounding the Horn, has been a vital centre for monotheistic faiths and cultural exchanges, shaping its legacy in both Islamic and world history.

#HornOfAfrica #IslamicHistory #AfricanCivilisation #ProphetSulaiman #QueenBilqees #Monotheism #EgyptianHistory #Nubia #Punt #AbrahamicTraditions #CulturalExchange #AfricaInIslam